Review of Netflix’s ‘Mo’

Reflections from an Iranian-Houstonian and Middle East Representation in film from Narratives of Resistance

Review of Mo, Season 2: where harsh reality & joyful humanity co-exist

At a time when Palestinian voices are intentionally being censored— from the violent arrests of student protestors on university campuses to Meta’s censorship of content about Gaza— the Netflix series Mo holds a remarkable place in simultaneously giving Palestinians and Houstonians representation. Mo Amer, a Palestinian-American comedian and actor, took the world by surprise when the first season of Mo came out on Netflix in 2022, showcasing a unique blend of cultures between Houston, Mexico, and connections to his Palestinian heritage (shown through a love for olive oil and his family in the show). But it was the highly anticipated season 2, released in January 2025, which touched people in unexpected ways.

Of course, the context of the ongoing genocide in Gaza is in the background of this, and as a Palestinian in the entertainment industry, Mo has inevitably been expected to speak out about this. As he centers his identity and tells stories about his family often in his comedy sets, understandably there’s a level of expectation when it comes to being a voice for his people. At the same time, it also makes me think about how people with marginalized identities are often thrust into this role of being a spokesperson on political issues affecting their people in ways that white celebrities never have to grapple with. There were times Mo has been criticized for his lack of speaking out about Gaza as the bombardment continued throughout 2024, however I appreciate the fact that when he does speak about it he always does so in the context of the 75-year occupation of Palestine, and not as an isolated event. And this is exactly how (pre-Oct. 7) Palestine is conveyed in Mo season 2, which perfectly captures both the beauty of Palestine and the pain of the occupation.

In the same vein, the show’s Jewish executive producer, Harris Danow has said in an interview “the Israel-Palestine of it all is something we intentionally avoided in Season 1…not because of the politics, but because the only thing people really know about Palestinians from the outside is their relationship to Israel and the occupation.” The focus of Mo, instead, was on humanizing them. But in season 2, there’s no avoiding the occupation and the politics of oppression in general. As an Iranian-American, I relate deeply to the lack of representation and humanization of my people and culture, and seeing the scenes from Mo in Palestine made me emotional because I’ve never witnessed the Middle East represented in such a nuanced and honest way. A scene that stood out to me was when he goes to a local mosque and prays, which gave me goosebumps because I never imagined I’d see Muslims represented in such a normal way. Islam has historically only been showcased in plots related to terrorism or in other Orientalist ways (more on this later), so the inclusion of this scene and the plotline was so simple yet so impactful.

On the other hand, as a Houstonian, I also appreciated the scenes filmed in Houston, in familiar streets and neighborhoods that boast the diversity of the city. Another scene seeped with meaning for me was when Mo’s car breaks down as he’s outside of the city at the ranch where his family has been producing olive oil. He has to make his way back home without a car in a city that’s notoriously car-reliant and lacks good public transit or walkability. Not to mention, the hot weather we experience most of the year, which I could feel as I watched Mo embarking on his journey home through various Houston landmarks, including NASA and Hermann Park. When he finally arrives home, he lays on the floor and his mother joins him in a scene that exudes resilience even in defeating moments.

It’s important to note two things, first that Mo is based on his real life, navigating his family’s displacement from Palestine, then being a refugee of the Gulf War in Kuwait, and eventually making his way to Houston where he was undocumented. Secondly, Mo had a high level of creative control over the show, as he co-created, co-produced, and co-wrote the show with Ramy Youssef, which shines through in the cultural nuances and emotion he’s able to convey. It’s clear that so much intention and awareness was brought to how this show would be an opportunity to combat negative stereotypes and dehumanization of Palestinians (and Arabs/Middle Eastern people more broadly) that is pervasive in Western media. Considering the fact that this is the first and only show about a Palestinian family, Mo has discussed “feeling the gravity of the situation” and how important it was to him to do this story justice and give people a point of reference to humanize Palestinians. My respect for Mo grew in watching this season because of his willingness to face these challenges and fight for creating a show that has made so many marginalized people feel seen, from Houston to Palestine.

“There’s no other Palestinian TV family to watch, to relate to or to feel any kind of love toward.”— Mo Amer

But what truly makes Mo stand out is how it combats all the heaviness of topics like immigration and occupation with comedy in ways that make them digestible, relatable, and even joyful. Mo shared in an interview that comedy is what saved him, saying “it’s my immediate instinct to joke whenever I felt sad.” A scene that demonstrates this is when Mo’s mother and older sister in the show are sitting together having an intimate conversation after their thanksgiving gathering, and the mom keeps checking her phone and mulling sadly over news about Israel destroying schools in Palestine. “We owe it to them to live, too.” Her daughter tells her, “We’re more than our pain and suffering, Mom. You wouldn’t know that watching this news.”

Honestly, the final episodes of this season had me in tears on several occasions, which I didn’t expect. But the tears were balanced out with laughter, especially when I had the privilege to see Mo do live comedy set in Houston. He touches on the themes in the show in his comedy sets, too, but in person he’s even more down-to-earth and relatable. Being in his home city always offers us unique opportunities to interact with him as an audience, and one person in the crowd was telling him about how he never expected to see the neighborhood he grew up in (Alief) on Netflix. Mo replied by noting how funny it feels to have Latinos from Alief tell him that and Arabs also telling him the same thing about seeing a family speaking Arabic on Netflix, and Palestinians telling him the same thing about seeing Palestine represented on Netflix. This blend is exactly what gives the show its multifaceted and one-of-a-kind flavor. Interestingly while I was working on this piece, I also got to see Ramy Youssef’s comedy show on his love beam 7000 tour, and after seeing both of these comedians perform I was astonished at their talents both as writers on the show, and as on-stage acts themselves. Both Mo and Ramy’s live sets reminded me of the impact of storytelling and joy as a form of resistance against colonial oppression.

Mo’s Origins: Comedy as a Tool of Resistance

Mo was first introduced to stand-up comedy when his older brother brought him to watch Bill Cosby perform at the Houston Astrodome in 1991. He was fascinated at how Cosby was able to command and work the crowd of 60,000 Texans, eliciting laughs and cheers at a cleverly-timed punchline or cheeky glance to the side. Mo noted that Bill Cosby was “destroying from nosebleed seats on down. He was on a rotating stage sitting down on a chair and talking into a lapel mic.” That was no easy feat considering by 1991, the city had almost 30 years of stand-up history and hosted stages for some of the country’s biggest comedians, such as the Texas Outlaw Comics. Mo sat in one of the largest venues for comedy at the time and resolved to pursue that as a career.

Four years later, Mo began skipping his 9th grade English classes as he coped with the death of his father. His teachers, Mrs. Reed and Mrs. Broderick at that time asked about his comedic career aspirations and negotiated: if Mo kept his attendance in check and participated in class, then he was allowed to practice his stand-up routines every Friday. His first sketch involved lots of physical comedy while playing an Indian pizza delivery guy much to the delight, and laughs, of his classmates. Before long, his English teacher brought Mo to the school’s theatre arts department and urged the teachers to include him in school productions. He played Pseudolus in ‘A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum’ and continued practicing his stand-up routines for other classes, often integrating class material into his jokes.

Mo immediately threw himself into every comedy club available in Houston following his high school graduation. His relentless nature in pursuing comedy eventually paid off when he became a finalist in the wild card round of Houston’s Funniest Person Contest on 9 June 1999. Steve Stricklin, the eventual winner of the contest, urged Mo to pitch his act at the Comedy Showcase. Mo walked up to Danny Martinez, the owner of Comedy Showcase and performed there the following week. He stayed at the Comedy Showcase and under Martinez’s tutelage before becoming a headliner himself.

Mo gained more popularity in 2006 after meeting Preacher Moss and joining the comedy troupe, Allah Made Me Funny, modeled after Spike Lee’s ‘The Original Kings of Comedy’. Their shows offered non-Muslims a chance to learn more about Islamic cultures as well as for other Muslims to share jokes about their own lives. Especially after 9/11, the group aimed to break down racial stereotypes, to break down barriers, and to use comedy as a medium for tolerance and acceptance between people. Their most popular jokes were about common Muslim stereotypes, 9/11, religious holidays, family, marriage, and the complications of being Muslim in post 9/11 America.

For Mo, much of his observational comedy relied on his immigrant life story, growing up in America and traveling the world for 20 years without a passport, even having Bradley Cooper unintentionally rescuing him in the Middle East and thinking he was being recruited into the Illuminati while sitting next to Eric Trump in 2016. It was important to him to use storytelling to build strong relationships, create emotional moments, and to give new perspectives as a Palestinian refugee. His stand-up routines became a cathartic experience for him and Mo was increasingly met with moments of “remorse, some cried on my shoulders, some had a lot of respectful things to say… Some were just acknowledging how wrong they were about the projections they had upon the region and the friends they made [local, Arab and Muslim], they found to be like, really profound moments.”

“Stand-up comedy, to me, is about being real, about being honest. If you’re not real, people will sniff that out.” —- Mo Amer, in an interview with NPR’s Ophira Eisenberg

Mo learned the importance of being genuine from both Danny Martinez and Dave Chappelle. Martinez advised Mo to write clean, universal material and Chappelle taught him to speak his truth. If he was not staying honest and truthful to himself, Mo believed that he became “a joke within a joke”, and that his grandparents would have been ashamed of him for pretending to be something he was not.

The Making of Mo: a Local Cast and Crew

Again, Mo’s writer’s room has a diverse group of Jews, Muslims and Christians— a group that may result in tension, but their commitment to the show and Palestinian perspectives transcended these religious identities. When they discussed plot points and storylines, the crew asked themselves if season two of the series should reflect the events of October 7 and the horrors that followed. “It was extremely difficult, that is the softest way I can put it. It was grueling— mentally, spiritually, physically,” Mo shared. In the end, the 2023 genocide was kept out of the show’s semi-fictional world because if not, the show “would make it seem like everything [that affected Mo’s family] started with October 7, and that couldn’t be further from the truth.”

The geopolitics, although extremely significant in creating the context of which both Mo’s live in, simply sit in the series’ background as humour and character development occupy the front. In Mo’s perspective, the show’s advantage was its ability to highlight the complicated day-to-day issues that Palestinians faced, like extreme scrutiny at checkpoints and intimidation by Israeli settlers. More importantly, it can be argued, is the show’s portrayal of how difficult it can be to enter the West Bank and to live there as a Palestinian.

As the showrunner, Mo Amer knew he had an immense responsibility to do justice when representing his community of Palestinians, refugees and immigrants. This burden of representation, coupled with both Palestinian and non-Palestinian opinions of what the show should talk about, forced the crew to outdo themselves with the quality of work they created. He lamented that it was “wildly overwhelming” to be a mouthpiece for Palestinians, because “whenever you do actually try to articulate a particular thought… you’re never going to make anyone happy. It’s difficult, but it’s always been my practice to articulate said message through my heart.”

To use his show as a way to communicate and represent Palestinians, it becomes especially clear that he has a close relationship with those in the writing room. This started with Mo seeking out Ramy Youssef to be the co-creator of his titular show. Youssef, a Muslim-American comedian and actor born to Egyptian and Palestinian parents, created and produced his own semi-autobiographical Hulu series ‘Ramy’ in 2019. It starred Youssef himself as a first-generation American Muslim in a politically-divided neighbourhood in New Jersey, and the challenges of his Muslim lifestyle against the judgment of his friends and family. Although they were already friends in 2015 through stand-up comedy, Mo and Youssef grew closer while shooting Ramy— Mo was casted as Ramy’s cousin who owned a diner.

In regards to show-making, Mo and Youssef connected through Youssef’s desire to portray scenes that were not normally represented in mainstream media. “When characters were not an outright negative depiction of Arab Muslims”, Youssef noted, “they were second- or third-tier characters and mostly part of something that wasn’t about them. Looking at an Arab Muslim family as real people with complex inner lives and quirks like any other family was just the beginning.” It was extremely important for Youssef that a viewer who did not have a good opinion of Muslims to watch his show and realize they were not so different from each other. To do that, Youssef believed it was important to take some time to examine the characters: “I personally think the only way to get the perspective of the character, or to represent them, is to have the camera linger on them in moments of silence. Because that’s what really tells you about what’s going on in someone’s head. When you get to have quiet moments alone with them”.

Both Mo and Youssef shared a belief that comedy was a place to explore the subconscious. There was a lot of trust in their collaborative process because to them, storytelling in both stand-up and show-writing was not just to make the audience laugh, but also to think. Storytelling was to deliver certain truths. There was a sense of awakened thoughtfulness behind the lines they wrote together,. It was this tight bond forged by years of friendship that allowed Mo and Youssef to uncover the deeper vulnerabilities that lay beneath certain themes, such as when Youssef picked up on Mo’s desire of talking about his father— a pivotal moment in the show.

“This is a love letter to Palestine. This is a love letter to my family. This is a love letter to Houston. It has all those components, but also it's for everyone. My Latino brothers and sisters who are dealing with the same type of situations. I wanted to show the absurdity of the detention centers in Season 2 and talk about how difficult it is to actually cross the border, and show how privileged even my character is in relation to other refugees and asylees in the country. It's for everybody. It's for everybody who's struggling to feel like they belong and to constantly fight just to be themselves and have an opportunity to grow with their families.” — Mo Amer, in an interview with Salon

Orientalism in Films: Contrasting History with Mo’s Self-Representation

In renowned Palestinian academic Edward Said’s book, Orientalism (1978), he argued that all Western studies into the regions of Asia and North Africa would depict them in a shrewd manner. In Said’s arguably most-influential book, he analysed how Middle Eastern societies were described by European “experts” in the 18th-19th century in ways that delighted the western imagination, while dehumanising the people it fed upon. He started with Napoléon’s 1798 invasion of Egypt, where scholars traveled to collect as much information about Egypt as they could. The underlying meaning behind ‘orientalism’ was the exaggeration of difference between the East and the West, the presumption of Western superiority, and the application of these stereotypes onto the Middle East. Instead of being an objective field, Said argued that these inherent qualities made Oriental studies (of the Middle East and North Africa, MENA) a mechanism to serve political ends.

“It has less to do with the Orient than it does with ‘our’ world…

The development and maintenance of every culture require the existence of another different and competing alter ego.” — Edward Said, Orientalism (1978)

Perhaps Said’s strongest argument is that Orientalism systematically produced a false description of Arabs and Islamic culture. By looking at Islamic societies and MENA regions as static, frozen in time and place, European scholars in the 19th century have neglected the dynamic and innovative cultures. Instead, scholarship increasingly began to codify Arab societies into certain essential qualities— something that Said noted, that nobody today would dare talk about black people or Jews with such essentialist clichés (in other words, stereotypes). Said continued to argue that Orientalism depicted Islamic societies as a homogenous monolith, and that Islam possessed a certain unity, rather than the reality of being varied and nuanced across different countries and communities. As a result, most Orientalist knowledge, and much of the world’s Eurocentric knowledge hegemony, was argued to be based on distorted and outdated beliefs.

“Reel images have real impacts on real people.” — Jack G. Shaheen

Western films have typically portrayed an ethnocentric perception of Arabs; instead of an authentic and realistic depiction of Arabic cultures, religions, dialects, and traditions. Common portrayals of Arab characters from non-Arab filmmakers include speaking in a heavy accent, being hostile and vicious, and these characters are usually in terrorism-centred plots. What, then, would make a film ‘Arab’? Film scholar and filmmaker Viola Shafik argues that since the Arab region is large and diverse, the term ‘Arab’ itself can be interpreted from colonial, Orientalist, and Pan-Arab perspectives among others. In the end, Shafik emphasizes that the Arab region comprises of ethnic and linguistic diversity, religious diversity, as well as geographical and historical differences. When analyzing films with Arab characters, it is therefore important to understand who the filmmakers are, and how their backgrounds influence their regional understandings of the Arab culture they aim to depict.

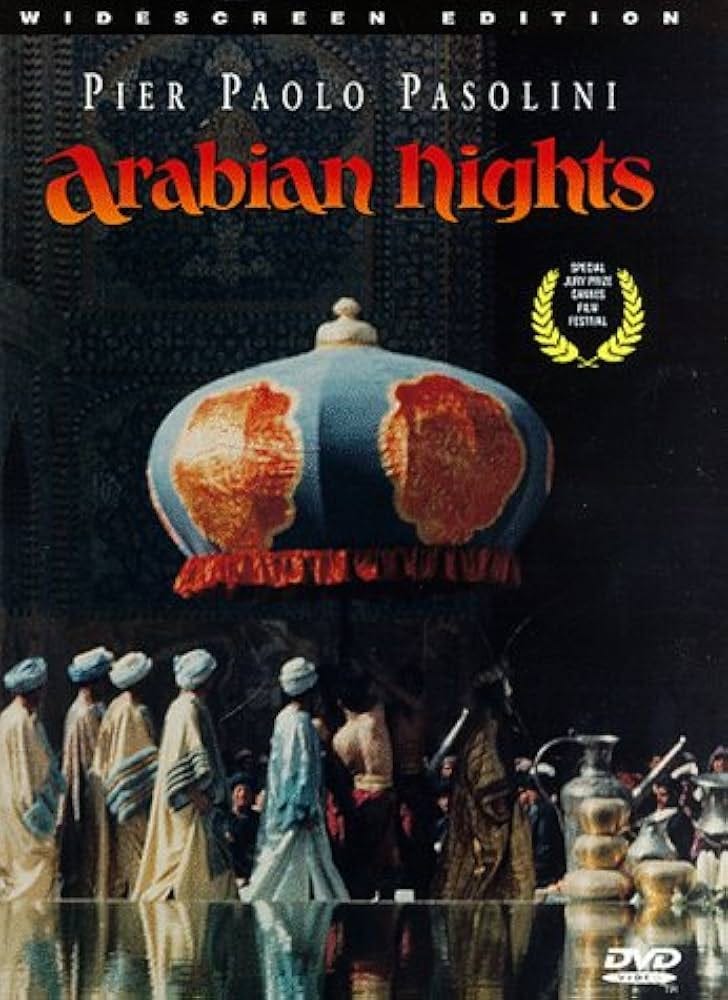

From the 1930s to 1970s, the golden age of Hollywood depicted Muslims and the religion of Islam through an Orientalist lens, because Western nations still had a large social influence in the Middle East. Films like ‘Arabian Nights’ (1974) and ‘The Thief of Baghdad’ (1961) depicted Middle Eastern culture as exotic and otherworldly with genies, flying carpets, magic lamps and heroes. Arabs were not cast in these films, but rather white actors would dress up in costumes and adorned in ‘Arabic make-up’. However, there began a movement towards realism in cinema in the early 1960s and companies started to cast real Arab actors. ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ (1962) and ‘Khartoum’ (1966) flooded the theatres and films started to showcase historical events, like the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans in WWI and the 1885 siege of Khartoum by Sudanese Muhammad Ahmed. This period gave rise to Mohammad Yachteen, who was the first Arab-American actor who starred in over 500 pictures.

Cinematic realism continued through the 1980s and 1990s, where political events of terrorism, Arab nationalism, and colonial resistance took centre stage— around the same time of the Iranian Revolution and the rise of the Palestinian Liberation Organization. American audiences needed Muslim villains for their beloved Hollywood heroes to defeat. These films reflected USA’s foreign policies and the American military-industrial complex.

After 9/11 and following a prolonged period of unrest in the region, many Hollywood films emerged with plot lines about the war on terror, the Middle East, and their own portrayal of Arab people. In these films, all Arab-Muslims were portrayed as dark skinned, violent and murderers, with some films even showing scenes that explicitly explained how Islam and Muslims were a threat to Westerners. Hollywood’s extremely negative portrayals of Arabic characters were not just offensive, but could arguably be considered as propaganda. They often generalized that all Arabs were terrorists and that Islam was a violent and oppressive religion.

However, Mo as a Netflix show avoided these negative stereotypes and instead, simply painted Arabs as who they were: people. By having the main creator be a Palestinian himself, as well as a dedicated, handpicked writing team, cast and crew, Mo takes a gigantic step towards self-representation and correcting these Hollywood mistakes. Mo Amer and Ramy Youssef (among many others) are able to make full use of their creative control and add their own voice in a traditionally white media landscape. It is more than brave— the team has been dedicated and meticulous in the details they chose to portray and set in Houston, Texas. From diasporic elements, racial diversity and scorching hot weather, it is clear that everyone involved was conscious of the meaningful impact that the show would have on its viewers.

This was such a lovely read and well-researched piece. Thank you for sharing❣️👏🏽

such a brilliant analysis, thank you both for sharing